Recently, I was awarded a R01 grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to conduct a full-scale clinical trial of Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement (MORE) as an intervention to reduce chronic pain and prescription opioid misuse in primary care. This five-year study will compare the efficacy of MORE to supportive therapy for 260 chronic pain patients receiving long-term opioid therapy who are at risk for opioid misuse.

Recently, I was awarded a R01 grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to conduct a full-scale clinical trial of Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement (MORE) as an intervention to reduce chronic pain and prescription opioid misuse in primary care. This five-year study will compare the efficacy of MORE to supportive therapy for 260 chronic pain patients receiving long-term opioid therapy who are at risk for opioid misuse.

Opioids may be medically necessary for some individuals experiencing prolonged and intractable pain, and most patients take medicine as prescribed. Unfortunately, opioids rarely completely alleviate chronic pain, and when taken in high doses or for long periods of time, can lead to serious side effects, including death by overdose, as well as risk for opioid misuse, which affects about 1 in 4 opioid-treated patients. Misusing opioids by taking higher doses than prescribed or by taking opioids to self-medicate negative emotions can alter the brain’s capacity for hedonic regulation, making it difficult to cope with pain (e.g., causing hyperalgesia – an increased sensitivity of the nervous system to pain) and experience pleasure in life (e.g., reducing sensitivity of the brain to natural reward). As such, non-opioid pain treatments that target hedonic dysregulation may be especially helpful for reducing chronic pain and prevent opioid misuse.

Multiple studies suggest that MORE improves hedonic regulation in the brain, resulting in decreased pain and an increased ability to savor natural, healthy pleasure. People who participate in MORE show heightened brain and body responses to healthy pleasures, and report feeling more positive emotions by using of mindfulness as a tool to enhance savoring. These therapeutic effects of MORE on savoring may be critically important, because findings from several studies show that increasing sensitivity to natural reward through savoring may lead to decreased craving for drugs – a completely novel finding for the field of addiction science (Garland, 2016). Our NIDA-funded R01 will provide a rigorous test of whether MORE improves chronic pain and opioid misuse by targeting hedonic dysregulation.

In our NIDA-funded R01, patients are receiving MORE at community medical clinics throughout Salt Lake City. Providing MORE in the naturalistic setting where most chronic pain patients seek medical care will make the therapy accessible to the people who need it the most. Ultimately, my hope is that this project will advance a new form of integrative healthcare, in which doctors and nurses work alongside social workers and other behavioral health professionals to help patients reclaim a meaningful life from pain.

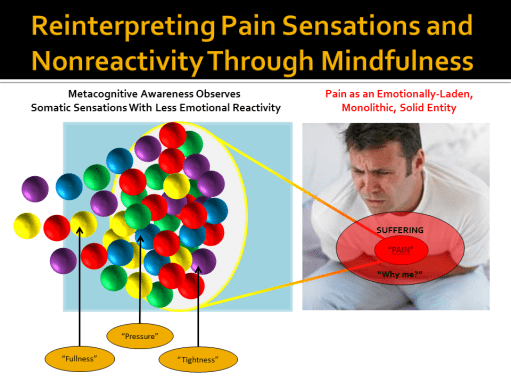

Chronic pain is often treated with extended use of opioid analgesics, yet these drugs can alter the brain in ways that may make it difficult to cope with pain and may reduce the experience pleasure in life. Mindfulness-based interventions appear to be a promising means of addressing these issues, but research is needed to understand how such interventions change the brain to reduce suffering.

Chronic pain is often treated with extended use of opioid analgesics, yet these drugs can alter the brain in ways that may make it difficult to cope with pain and may reduce the experience pleasure in life. Mindfulness-based interventions appear to be a promising means of addressing these issues, but research is needed to understand how such interventions change the brain to reduce suffering.